Freeze, Vacuum, Blinding Sun: Ace Pro 2’s Stratosphere Test

Freeze, Vacuum, Blinding Sun: Ace Pro 2’s Stratosphere Test

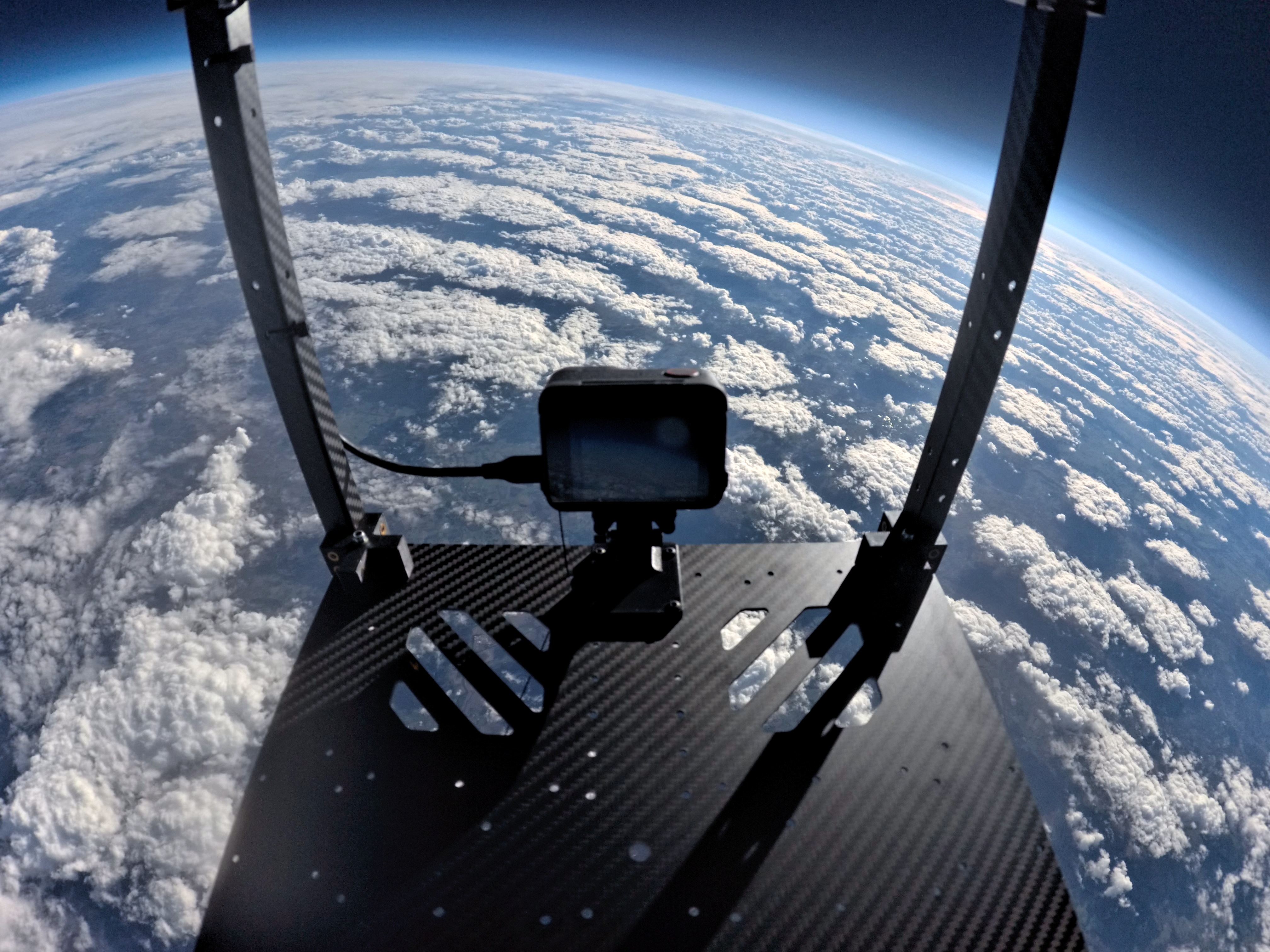

Freeze. Near-vacuum. Blinding sunlight. At 38 km above Earth, a tiny mistake can turn everything into a black screen. This is the cinematic story of how Insta360 Ace Pro 2 was sent into the upper stratosphere—and what it took to bring the footage back alive.

It starts like a dare you shouldn’t take seriously.

A camera. A capsule. A balloon.

And a team that, somehow, has already sent far stranger things upward—objects you’d never expect to meet the edge of space.

But this time, the “payload” isn’t a stunt for laughs. It’s an 8K action camera—Insta360 Ace Pro 2—about to be pushed into an environment where the rules change fast.

The people who don’t gamble—they model

Sent Into Space isn’t a weekend experiment. They’ve been doing commercial near-space launches since 2011, with 1,000+ flights into the upper stratosphere. Aerospace engineering, video production, marketing—their work sits in the overlap.

That experience doesn’t remove risk. It just moves the risk earlier—into planning.

Because on launch day, the real tension isn’t “Will it fly?”

It’s “Where will it land… and will we get it back?”

Location first. Balloon second.

They can launch from 15+ sites across the UK with short notice, choosing the best option based on weather and predicted flight path.

Then comes the part that feels like cheating: they build wind simulations using weather data pulled from 100,000+ sources worldwide, and tune the ascent speed, burst altitude, and descent to predict (and adjust) the landing zone—down to a few hundred meters at the moment of launch.

In other words: this isn’t hope. It’s math.

A quiet lift powered by hydrogen

No roaring engines. No fuel burn.

Their craft rises on hydrogen’s natural buoyancy, captured in biodegradable latex balloons—renewable hydrogen, no combustion, and no greenhouse gas effect from burning fuel. They also build components in-house with lower-impact methods like 3D printing and carbon fiber molding to reduce waste and shipping.

Peaceful, on paper.

And then the stratosphere starts stripping away comfort.

The kill zone: where cameras fail for boring reasons

At the peak of these flights, you’re in a near-total vacuum, above 99.5% of Earth’s atmospheric gas. Temperature sits around −65°C.

That cold isn’t just cinematic—it’s chemical. Batteries need insulation because reactions slow down at low temperatures.

And the vacuum creates a weird trap: electronics generate heat, but without air, they can’t dump it through convection. Cameras that rely on internal fans can’t “move air” that isn’t there—so teams often have to retrofit alternative heat dissipation methods.

This is where Ace Pro 2 gets its quiet advantage: Sent Into Space notes that Insta360 cameras don’t have that built-in fan element, and because of it they often capture the full ~2.5-hour mission—up and back—without fault.

The enemy you don’t expect: sunlight

Cold can kill. Vacuum can kill.

But lighting ruins missions in a more brutal way—because it doesn’t “break” the camera. It breaks the footage.

On Earth, sunlight is diffused by the atmosphere (that’s why the sky is blue). Above it, diffusion disappears. The sun appears almost 60% brighter, and exposure settings that were “fine” on the ground can become a disaster.

Sent Into Space says the biggest challenge is often the simplest-sounding one: mounting the camera perfectly to capture everything in the best possible light.

No second takes.

38 km: the moment the planet looks unreal

Then it happens.

Recommended

Insta360 Ace Pro 2

Insta360 Ace Pro 2 Dual Battery